|

FODFS guides many into adulthood by helping with education

Union-Tribune | May 13, 2005 | Lisa Petrillo, staff writer Georgette Todd is one tough sapling who has grown straight and tall, with the help of some surrogate mothers. Todd was 4 when a hit man shot her mother in an apparent meth deal gone sour. She was 13 when she overdosed on cocaine fed by her stepfather, Mad Dog, in between raping her. Weeks after he went to prison, her wheelchair-using mother, her once- spirited mother who was only 14 when she ran off with Todd’s father, died of an overdose of pain medication. That’s when the state of California become her parent, and it wasn’t pretty. In a memoir she’s writing about growing up the way no child should have to, Todd has this to say of the foster-care system: “We are in prison for crimes our families committed.” But along the way she met the jam-making Point Loma lady, the go-the-extra-mile social workers, the kindly nurse, the dedicated teachers, the motivational speaker and the busy innkeeper who have helped her write a happy ending to her story. They are the members of a grass-roots nonprofit group called Fostering Opportunities Dollars for Scholars, which “adopts” former foster youths trying to complete their higher education – a feat harder than scaling Half Dome for almost all of them. For the 100,000 children in California’s $3 billion-a-year foster- care system, college or vocational school is the least of their worries. Once they turn 18, the law calls them adults and the state generally cuts them loose. Most are on their own. Entirely. It happens every year for as many as 400 youths out of the 7,000 in San Diego County’s foster care. “When you turn 18, you become officially invisible,” Todd said. No one tracks what happens to former foster children, but the few statistics available are bleak. Nearly half are homeless within a year of turning 18; by age 20, 60 percent of the women will have been pregnant. Ten percent enter college. Georgette Todd beat the odds on all counts, with the help of her surrogate mothers. She became one of the less than 5 percent of former foster children who earn college degrees. Tomorrow she will earn her master’s degree in fine arts from Mills College in the Bay Area. She wants to be a writer and focus on foster-care advocacy because, she explained, “I live with these memories. I sit with them every day. I had to pursue this full throttle.” Todd was chosen to deliver the student graduation speech. At least three of her surrogate moms will be in the audience, applauding proudly. “All these strangers have done more for me than anybody in my family ever did. I’ve totally divorced myself from my blood relatives. They are my family now,” Todd said. From Georgette Todd’s unpublished memoir on her suicide attempt Dec. 25, 1994, soon after entering foster care: On Christmas day I wake up hating the world. The bullet, the marriage, the moving, the poverty, the trailers, the Salton Sea, the drugs, the rapes, the OD, the suicide and now foster care. I am an absolute orphan. An orphan. Orphan. How romantic. Cue the rescue. But there is no rescue. God will be too late, if he comes. He’s late now, he was late then. Three years ago, Ocean Beach innkeeper Katie Whalen Elsbree was having matzo ball soup at D.Z. Akins, the venerable east San Diego deli, with a friend and a friend of a friend. They shared the same frustration: Why doesn’t somebody help foster kids make the transition to adulthood? Elsbree had raised her own children and foster children before opening Beach Bed and Breakfast. She’d also taught in San Diego County’s alternative court schools, which educate foster kids as well as juvenile offenders. Over lunch, the three women created one of the only grass-roots scholarship programs of its kind in the nation for foster youths. Elsbree had long been active in Dollars for Scholars, a 45-year- old charity with more than 1,000 chapters nationwide providing college scholarships to the needy. So they launched a chapter for former foster kids under the national umbrella organization, Scholarship America. It’s all about the karma to Elsbree, who grew up one of 11 children in a family with no money to send a girl to college in the 1950s. She was married with children when she took a few college classes and caught the eye of a professor who recommended her for some private foundation scholarships. “What a boost that was,” said Elsbree, who with help got through college, graduate school and earned her teaching credential. “I always thought, ‘If I ever get the chance, I’ll pay this back.’ ” She’s been paying it back for decades by helping launch more than a dozen Dollars for Scholars chapters countywide. Her most ambitious effort has been Fostering Opportunities, which has collected more than $30,000 in donations and awarded scholarships to more than 20 former foster youths. Fostering Opportunities member Geri Shea said when she worked in the county court schools system, she saw so much suffering “I wanted to take the kids home and make things right. This is my way of doing that.” They raise money from walk-a-thons, dinners and grants from more established foundations like the Thursday Club Juniors, which awarded Fostering Opportunities the largest donation it has received to date. The dozen board members also raise donations through their collective business networks; fostering member Susan Clarke, a motivational speaker, plugs her group to business groups she deals with nationwide. Elsbree even hits up her bed-and-breakfast customers when she needs something. Since their incomes are often negligible, many former foster children qualify for financial aid at public colleges, meaning their tuition is waived or greatly reduced. But that still leaves food, books, rent, transportation and other costs. Fostering Opportunities scholarships plug the most pressing gaps, for example, providing one with a few hundred dollars for books, $500 for transportation costs for another, $400 tuition assistance for yet another. Since the all-volunteer Fostering Opportunities group has no central office, they rely on their network of high school counselors, social workers and teachers to send scholarship applicants their way. “We never turn anyone down, their stories are always so sad,” said Fostering Opportunities member Mary Jo Macomber, a nurse and Elsbree’s sister. Other scholarship programs for former foster children, including the Child Abuse Prevention Foundation Foster Fund, may give out more money. But Fostering Opportunities sweetens the deal with part-time mothering. They call. They write. They e-mail. They take them to lunch. They take care of the little details that few scholarships anywhere provide. Macomber sends her Fostering Opportunities daughter valentines. She sends her quarters for laundry. When the young woman who had spent her whole life institutionalized got to her college dormitory, she discovered she lacked such basics as bedsheets; it was Macomber who sent some pretty sheets her way. From Georgette Todd’s unpublished memoir: In the shower hot water dilutes your tears. Your face becomes hotter. Floods of warm water pierce the backs of your eyes. Your mouth is dry. Your head is congested. A rush of upset suffocates you. You can’t breathe because you’re hiccuping. Your body convulses. You cry into your hands so no one can hear you. No one can hear you. Andrea Humphress doesn’t talk much about how she was robbed of sound and speech by a relative who beat her so savagely when she was small that she permanently lost her hearing. “I was abused, sexually abused, physically abused. Many things negative have happened to me. But I turned out to be a happy and successful student that has big dreams for the future,” said Humphress, a cheerful, blonde 19-year-old who loves surfing and learning to cook. She’s studying auto mechanics with the dream of one day parlaying her skills into becoming an airplane mechanic. “Nobody can stop me,” Humphress said. She spent most of her life in foster care, the best years at the San Pasqual Academy in the countryside near the San Diego Wild Animal Park. The county of San Diego converted an old religious boarding school into a group home for foster teens. Through her academy counselor, she found Fostering Opportunities. It was over breakfast at a scholarship awards ceremony that Debbie Applebee, a special education teacher for the county’s alternative court schools, met Humphress and was instantly charmed. “I asked her what she needed, and she said, ‘I need shoes that have steel tips.’ ” Applebee “adopted” Humphress on the spot. Though she knows no sign language, they communicate via e-mail. Armed with the $500 scholarship, the pair went on a shopping spree like none either woman had ever been on. Humphress, for the first time in her life, got everything she wanted, and Applebee learned her way around a Pep Boys store as they scooped up steel-tipped boots, coveralls, socket sets and all manner of shiny tools that they hope will help seal a bright future for Humphress. Reprinted with permission from the San Diego Union-Tribune. |

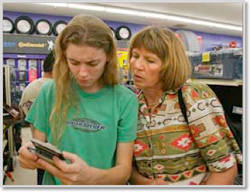

JOHN GASTALDO / Union-Tribune

Debbie Applebee looked over the shoulder of Andrea Humphress as they shopped for supplies that the 19-year-old needed for her auto mechanics studies. Humphress used scholarship money provided by Fostering Opportunities Dollars for Scholars, which helps former foster kids. JOHN GASTALDO / Union-Tribune

Katie Whalen Elsbree, an Ocean Beach innkeeper who raised and educated foster kids, got the idea for Fostering Opportunities while talking with two women over lunch three years ago. |